Painting Guide - Equipment

Having spent quite a bit of time, not to mention a few thousand words, prattling on about the colours (and paint codes) that I use to paint my toy soldiers, it is probably only right and proper that I discuss the hardware carried, and worn, by soldiers. This is an excuse to share lots of little bits of information that I have come across whilst researching my armies, and wider questions such as coat colours. Don't be surprised if there is a digression or three.

For those of you new to the blog here are the other posts:

Coat Colours Part 2: Royalist Regiments of Foot

The same account book gives the individual cost of a carbine as £1 4s 0d, just shy of £141.00 modern. Still less than the price of a horse (which was about £6, or 2 months wages).The Earl of Shrewsbury (whose home Hatfield was) paid £6 15s 0d for his buff coat (£800 modern, 2 and a half months wages), and £16 12s 0d for new armour (£1800 modern or 6 months wages).

That price for a carbine seems rather expensive, but I'm guessing that the wheelock mechanism is the pricey component. For comparison a matchlock musket with bandoleers was 16 shillings (£95 modern).

But I digress, buff coats varied in colour from mid brown to something more akin to the colour of buff paint sold in model shops. For the record I paint mine Foundry buff leather 7B for rank and file troopers, but also occasionally use rawhide 11B, tan 14B. Buff 7B looks particularly good washed with Citadel Agrax Earthshade.

Looking at the buff coats in the Littlecote Collection, sleeves appear to be attached to the body with laces. Admittedly Littlecote buff coats might be a regional pattern, but other surviving examples look to have the same construction.

Firearms

Musket rests varied greatly examples that I have seen have been either blackened steel, bare metal, or brass. I have yet to see a rest with its surviving woodwork.

I paint all firearms the same: woodwork is Coat d'Arms 219 chestnut brown, with Foundry metal 35B metalwork, and for a bit of variety Vallejo Game Color glorious gold for the brass tip of the ramrod visible, and for the butt of pistols. I use the same palette for musket rests: chestnut brown woodwork with brass forks (glorious gold).

Firelocks were a much rarer form of musket; an early version of what would become known as the flintlock musket, they were particularly suited to artillery guards (having constantly lit matches around gunpowder stores was abhorrent to even seventeenth century health and safety officers). The Royalist army had a number of firelock equipped units, which weren't specifically artillery train guards.

Dragons were a form of short musket which were initially used by dragoons (and believed to be the reason for their name).

Apostles are the supposed name for the powder charge cases (or more correctly called chargers) hanging from a musketeer's bandolier, so called because a musketeer had twelve of them. There is absolutely no contemporary evidence to support the name 'apostles'; the term is a one-off comedic description made in 1678 (March 1678, The Diary of Henry Teonge, published 1825) and, unsurprisingly, popularised by the Victorians.

Surviving bandoliers have either 12, 14 or 16 chargers: the number of chargers relates to the bore of the musket. The ordinary ammunition scale for a musketeer was a pound of powder, and a pound of shot. A 12 bore musket used 1/12th of a pound per charger, and the shot weighed 1/12th of a pound (1.3 oz or 37.8g). A 14 bore musket had 14 chargers each containing 1/14th of a pound of powder and shot weighed, you guessed it, 1/14th of a pound (1.14oz or 32.4g). I'll leave you to guess at the ratio for 16 bore...

Unfortunately these portraits appeared on hilts long before his death, but the Victorians didn't let a little thing like facts get in the way of romanticising one of the bloodiest episodes of British history. It must also be pointed out that many swords of this type had undecorated hilts.

Chirk Castle has a drum from 1670s.

Another drum came up for auction in December 2020, at Ader Maison de Ventes, Paris.

Another clue to painting drums hangs in the National Portrait Gallery, a portrait of Charles and his secretary Sir Edward Walker. Walker is using an oversized drum as a makeshift desk. The drum bears a coat of arms.

Caveat: these are my observations, with a smattering of references thrown in for good measure, they are in no way definitive. They could never be. The best we can ever aspire to, when modelling soldiers of the English Civil Wars, is a pastiche. This is what works for me. If it helps you out - great.

Personal Protective Equipment (to coin a modern term)

Buff coats were traditionally made from buffalo hide, but were invariably made from cow hide (not many buffalo roaming around Blighty). Modern day testing shows that they could take most sword blows without the wearer dying instantly.

Personal Protective Equipment (to coin a modern term)

Buff coats were traditionally made from buffalo hide, but were invariably made from cow hide (not many buffalo roaming around Blighty). Modern day testing shows that they could take most sword blows without the wearer dying instantly.

|

| Close up of fastenings of Gell's buff coat, Royal Armouries, Leeds |

Of course buff coats were not all made equal, let's look at the Littlecote Collection which has a large number of buff coats in its armoury. The Hatfield House accounts book of 1688 shows the cost of 5 buff coats as £11, (so £2 4s 0d per coat). Using the National Archive currency converter (1690 to 2017 is closest data available) gives a modern value of £263.00. So not the equivalent price of a sports car that wargamer facts would have you believe; admittedly a straight monetary conversion isn't necessarily the best translator of value, the NA converter also gives this as 24 days wages for a skilled tradesman (which equating to average modern day UK salary would be a cheap second hand car, expensive, and a significant outlay but not out of reach expensive). Remember that soldiers didn't have to buy their kit all in one go (the exception being many trained band soldiers), their colonels purchased the equipment, had it issued, then deducted equipment costs from soldier's wages.

Top of the range late C17th PPE - buff coat, lobster pot, front and back cuirass and riding gauntlet (technical name: vambrace) - the decoration on the armour would suggest this isn't for troopers (it belonged to King Pedro II of Portugal). On display at the Met, NYC. Made by London armourer Richard Holden, who made a very similar suit for James II, which is on display at the Tower of London.

The same account book gives the individual cost of a carbine as £1 4s 0d, just shy of £141.00 modern. Still less than the price of a horse (which was about £6, or 2 months wages).The Earl of Shrewsbury (whose home Hatfield was) paid £6 15s 0d for his buff coat (£800 modern, 2 and a half months wages), and £16 12s 0d for new armour (£1800 modern or 6 months wages).

That price for a carbine seems rather expensive, but I'm guessing that the wheelock mechanism is the pricey component. For comparison a matchlock musket with bandoleers was 16 shillings (£95 modern).

But I digress, buff coats varied in colour from mid brown to something more akin to the colour of buff paint sold in model shops. For the record I paint mine Foundry buff leather 7B for rank and file troopers, but also occasionally use rawhide 11B, tan 14B. Buff 7B looks particularly good washed with Citadel Agrax Earthshade.

Looking at the buff coats in the Littlecote Collection, sleeves appear to be attached to the body with laces. Admittedly Littlecote buff coats might be a regional pattern, but other surviving examples look to have the same construction.

Portraits of the great and good, show their buff coats with fancy sleeves – possibly fabric, possibly ribbon sewn onto buff, fabric overlaid buff, embroidered. Great for portraits but probably unlikely to offer much protection in battle. Did they have sleeves for best, and sleeves for war? Or did they have two coats – a fighting coat and a poncing around looking flash coat?

Sir Thomas Fairfax's buffcoat (in the collection of the Castle Museum York, sadly not on display) has braid attached to the sleeves -see here.

Buff was also worn to protect the wearer from rubbing of pikemen's corselettes. Full buff coats were pricey, sleeveless buff could provide the protection at a reduced cost. There are records of 'trained band buff', a sleeveless buff jerkin, being popular amongst members of trained bands (remember members of trained bands were expected to provide their own equipment). Records show that large quantities of trained band buff were taken as spoils by the Royalists from the London Trained Bands.

Footwear

Don't forget that footwear wasn't left or right foot specific. I paint all footwear a mix of browns - Foundry buff 7B, spearshaft 13B, deep brown leather 45B, Coat d'Arms wood brown 218, chestnut brown 219, chocolate brown 519, but my favourites are Humbrol dark earth 29, and natural wood 110.

Buff was also worn to protect the wearer from rubbing of pikemen's corselettes. Full buff coats were pricey, sleeveless buff could provide the protection at a reduced cost. There are records of 'trained band buff', a sleeveless buff jerkin, being popular amongst members of trained bands (remember members of trained bands were expected to provide their own equipment). Records show that large quantities of trained band buff were taken as spoils by the Royalists from the London Trained Bands.

Armour

Armour is an interesting topic - over the course of the Wars you can plot the development of warfare by how quickly armour levels changed. At the start of the Wars armour seemed to be 'wear as much as possible', an eminently sensible notion. However, cost, weight, fatigue, lack of manoeuvrability all figure and as the Wars progress armour starts being discarded until just core items are left.

|

| Littlecote Colection, Royal Armouries, Leeds |

Initially, the ideal level of armour for pikemen was a helmet of some sort (often a morion), back and breast plates and tassets - long flexible skirts.

Blackened full pikeman's armour, and morion, The Met, NYC

As the Wars progressed, a combination of supply issues and soldiers being soldiers meant that tassets were the first to be discarded, helmets came in short supply, as were breastplates. Pikemen could be seen in all stages from 'full armour' to 'no armour'.

Secrets were discreet armoured head protectors which were worn underneath a hat, there were two types, both can be seen at the Royal Armouries, Leeds.

But what colour? Armour wouldn't have been nice and shiny as it appears in movies. Armour was often blackened (a method of protecting it form rust which involves burning oil onto the metal) which gives a dull black appearance. To get this effect I have used two methods - the first involved painting armour with W&N black ink, which takes forever to dry and is susceptible to being rubbed off, this natural wear of the black whilst painting gives a good effect, but is messy. So I switched over to using Foundry blackened barrel 105B and 105A (slightly darker version) which give a really good finished appearance when washed with Citadel Nuln Oil, and is a lot less messy than using the ink method.

Close up of russeted pikeman's armour, Banbury Museum, Oxfordshire

The other common method of protecting armour from rust, was called russeting which gave a reddy brown colouration to armour - the armour was encouraged* to develop a light rust then oiled to protect from further rust. I think I have finally hit upon a 'recipe' for russeted armour: base coat of Foundry bronze barrel 103A then wash with Nuln Oil. November 2022 update: I have since tweaked how I paint russeted armour, hopefully my experiments may help you formulate your own 'recipe'.

I have painted my units of cuirassiers using all three of these Foundry colours in order to break up the monotone. The difference, after a heavy Nuln Oil wash, is very subtle.

Full cuirassier suit, Turton Tower, Lancashire

If you finish your figures with a Matt varnish, it is worth adding a satin varnish finish to the armour. Gives it a bit of a shine, but not too much.

Cavalry armour started as full cuirassier suits but was quickly dropped in favour of harquebusier armour - a buff coat, with back and breast plates, helmet, and for officers an armoured riding gauntlet, or to give it its proper name - a vambrace. There's no evidence that vambraces were issued to troopers, post-1670 documents note their issue to officers only.

Fishscale vambrace, Royal Armouries, Leeds

Of the armoured vambraces that I have seen the vast majority have been metal, one was made of fishscale buff - a system of many layers of overlapping buff cut to resemble fish scales. The National Army Museum has a fishscale upper riding arm protector. (No idea what the technical name for this is, possibly a rerebrace, or even a pauldron. I think rerebrace is closest.)

Vambrace and fishscale upper arm protector, NAM, London

Footwear

Sir Thomas Fairfax's riding boots, National Civil War Centre, Newark

Don't forget that footwear wasn't left or right foot specific. I paint all footwear a mix of browns - Foundry buff 7B, spearshaft 13B, deep brown leather 45B, Coat d'Arms wood brown 218, chestnut brown 219, chocolate brown 519, but my favourites are Humbrol dark earth 29, and natural wood 110.

Hats

Apparently it wasn't Godly for anyone to be seen without a hat, which is a good excuse not to do lots and lots of bareheaded headswaps. But if you visit any re-enactment events you'll regularly see individuals scrabbling around on the ground looking for their hats. So a few hatless Godless individuals will always be required.

Most brimmed hats were felt, so could be any number of colours. Monmouth and Montero caps are both made from wool, so they too could be any colour the owner desired.

A number of hats from the period exist. All of which, somewhat unhelpfully, are brown.

Cromwell's hat, Cromwell Museum, Huntingdon

A slightly later 1660/1670 hat, Banbury Museum, Oxfordshire

| |

|

Monmouth cap, The Nelson Museum and Local History Centre, Monmouth

Firearms

Matchlock muskets, part of the Littlecote Collection, Royal Armouries, Leeds

(if you are wondering why the shadows seem a bit weird - they are displayed upside down as they were at Littlecote House, I've inverted the picture so they are the right way up)

The vast majority of musketeers fought with matchlock muskets. So called because the firing action moved a lit match to ignite gunpowder in a pan (the source of the saying 'flash in the pan') which in turn ignited the gunpowder in the barrel of the musket. At the start of the wars these muskets were often 4 feet in length, and their weight necessitated the use of musket rests. Shorter (and much lighter) muskets started appearing from 1643. Shorter muskets, without rests, had been recommended by the Board of Ordinance in 1640, but they weren't readily available. Examples in museums tend to be dark brown (akin to brown bess muskets of the nineteenth century) with bare metalwork. The weight of muskets lent itself to the utilisation of the musket as a club during close combat - there are many recorded examples of soldiers using muskets as clubs in battle.

Musket rest fork, Warrington Museum and Art Gallery

Musket rests varied greatly examples that I have seen have been either blackened steel, bare metal, or brass. I have yet to see a rest with its surviving woodwork.

I paint all firearms the same: woodwork is Coat d'Arms 219 chestnut brown, with Foundry metal 35B metalwork, and for a bit of variety Vallejo Game Color glorious gold for the brass tip of the ramrod visible, and for the butt of pistols. I use the same palette for musket rests: chestnut brown woodwork with brass forks (glorious gold).

There is a contemporary reference to Sir Beville Grenville mustering his Regiment on Bodmin in August 1642: "very discernible for that the pikes and (musket) rests are all painted with white and blue" (True Proceedings of the Severall Counties... August 1642 BL TT E114/6)

Dragons were a form of short musket which were initially used by dragoons (and believed to be the reason for their name).

Carbines from the Littlecote Collection, Royal Armouries, Leeds

Carbines were short light muskets which had been designed to be used on horseback. Pistols were the preserve of cavalry; both they and carbines used a wheellock (sometimes called doglock) mechanism, which was a clockwork mechanism which required winding up with a spanner before it could be fired. Upon firing the wheel would spin against a piece of iron pyrites producing a spark (a bit like a cigarette lighter).

Matches were lengths of cord which had been soaked in saltpetre, effectively becoming a very slow burning fuse. Matches posed a number of problems: prone to going out in very wet conditions, their glow would be a giveaway of troop positions during the night. Although Waller's men used this to good effect at Lansdowne, they left burning matches on a wall during the night to trick the Royalist army into thinking that they were holding their position, when in fact they were retreating towards Bath. Match cord was usually made from flax or hemp - I paint mine Coat d'Arms unbleached wool 240, which gives quite a nice look when heavily washed with black.

Matches were lengths of cord which had been soaked in saltpetre, effectively becoming a very slow burning fuse. Matches posed a number of problems: prone to going out in very wet conditions, their glow would be a giveaway of troop positions during the night. Although Waller's men used this to good effect at Lansdowne, they left burning matches on a wall during the night to trick the Royalist army into thinking that they were holding their position, when in fact they were retreating towards Bath. Match cord was usually made from flax or hemp - I paint mine Coat d'Arms unbleached wool 240, which gives quite a nice look when heavily washed with black.

Apostles are the supposed name for the powder charge cases (or more correctly called chargers) hanging from a musketeer's bandolier, so called because a musketeer had twelve of them. There is absolutely no contemporary evidence to support the name 'apostles'; the term is a one-off comedic description made in 1678 (March 1678, The Diary of Henry Teonge, published 1825) and, unsurprisingly, popularised by the Victorians.

Bandolier and chargers on display at Les Invalides, Paris

Surviving bandoliers have either 12, 14 or 16 chargers: the number of chargers relates to the bore of the musket. The ordinary ammunition scale for a musketeer was a pound of powder, and a pound of shot. A 12 bore musket used 1/12th of a pound per charger, and the shot weighed 1/12th of a pound (1.3 oz or 37.8g). A 14 bore musket had 14 chargers each containing 1/14th of a pound of powder and shot weighed, you guessed it, 1/14th of a pound (1.14oz or 32.4g). I'll leave you to guess at the ratio for 16 bore...

Bandolier and charges, Royal Armouries, Leeds

There is a contemporaneous reference to blue powder charges: an order for the supply of a number of bandoliers for the New Model Army (Museum of London Tangye Collection MS 46 78/708: transcribed by Gerald Mungeam ‘Contracts for the supply of equipment to the ‘New Model’ Army in 1645’, Journal of the Arms and Armour Society vol.6 no.3 (Sept 1968)) - the chargers to be blue, and on blue and white string (good luck painting that on 15mm figures).

There is also a newly unearthed reference to Sir Richard Vyvyan's Regiment in 1643. This Cornish regiment of foot were issued black 'Bandaleres' with red belts (Cornish Records Office DDV EC/1/5).

The vast majority of surviving 'apostles' don't have any evidence of being blue (one illustrated appears to be the exception to the rule), they do show evidence that they were oiled to make them waterproof.

|

| Priming flasks, Royal Armouries, Leeds |

Musketeers would also carry a priming flask, a shot pouch, as well as a bag (called a snapsack) containing their personal possessions and food /drink.

As I'm lazy I paint chargers, bandoliers and all leatherwork (straps and bags) on musketeers Coat d'Arms wood brown 218.

Edged Weapons

Cavalry often carried mortuary swords, which alas, is yet another Victorian term with no basis of being used in the seventeenth century. It is a good term though, because it is so much quicker typing or saying "mortuary sword" than "basket hilted broad sword", which is the proper name for the sword. Knowing the true name of the weapon tells you all you really need to know about it (straight, broad blade, with a basket hilt handle guard). Many featured a portrait of a man, which was believed to be King Charles by the Victorians, and his appearance on the basket hilts an act of memorialisation of his execution.

|

| Close up of 'mortuary sword' portrait Royal Armouries, Leeds |

'Mortuary swords' on display at Nantwich Museum

Pikemen, dragoons and musketeers often carried hangers - short cutlass style swords; or short tuck swords - a shortened version of a long sword designed purely for stabbing (it didn't have a sharpened edge).

I paint all swords the same Foundry metal 35B metalwork, and for a bit of variety Vallejo Game Color glorious gold for basket hilts (a good rich colour that looks like brass when used in small doses on 15mm figures). Scabbards, and sword handles are just painted black, posh people might get fancy decorated scabbards though.

Halberds and a partizan , Broughton Castle, Oxfordshire

(ignore the much later spontoons at either end of the rack)

Pikes, partizans and halberds** are painted Coat d'Arms chestnut brown 219, with Foundry metal 35B metalwork. Halberd tassles have to be painted red in my book Coat d'Arms russet red 237 or Foundry madder red 60B, as they are always red in films and museums (no doubt a result of the Victorians again).

A note about pikes: you will often see the Wargamer Fact™ about pikes being cut down by pikemen. Carrying a very long, unwieldy pointy stick for weeks on end will have been very hard work. Applying the principle of Occam's razor, and it is not too much of a leap of faith to make the assumption that pike shortening took place. But what evidence exists for such a practice? The Covenanting Army marched around a lot more than any other army, and there was an occasion when they lost a fight against Irish pikemen because their pikes were shorter than the Irish pikes. General Monck complained about pikemen shortening their pikes (he complained about a lot of things, many of his complaints appear to be unfounded). But. And that is a big but; pikes were tapered along their length to stop them bowing, and also to make them easier to use. Trimming a couple of feet off their length would make a tapered pike very unwieldy. If you'd like to fall down a rabbit hole on the interesting subject of the 'queen of weapons' see here.

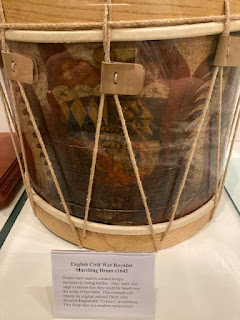

Drums - a handful of drums from this period survive. A slightly older drum - 'Drake's Drum' is on display at Buckland Abbey, the Royal Armouries has a 'Dutch' drum from the 1640s.

|

| Dutch drum Royal Armouries, Leeds (the crown and ciphers may be a later addition) |

Chirk Castle has a drum from 1670s.

|

| Drum, Chirk Castle |

The Combined Military Services Museum has a drum claimed to be 'Royalist' from 1645 - the coat of arms appears German from a century later (possibly Duke of Württemberg-Winnental?).

|

| 'Royalist' marching Drum, CMSM |

|

| Reverse side of the drum, not normally on display. Photo courtesy of CMSM |

|

| Close up of the armorial. Photo courtesy of CMSM |

Another drum came up for auction in December 2020, at Ader Maison de Ventes, Paris.

|

| Photo from the Ader online auction catalogue |

|

| Photo from the Ader online auction catalogue |

The drum skin claims provenance of belonging to Sir Thomas Culpepper and that the drum was captured at Colchester. However there are a few issues with the claim. The armorial is correct for the Culpepper family, but Culpepper's Regiment of Foot were not present at Colchester - his Regiment of Horse were, but not his foot. The text on the skin claims that the drum was hung in Leeds Castle - the Castle was inherited by Sir Thomas's son Sir Cheney Colepepper, who fought for Parliament. Did the drum belong to him? Alas we do not know what has become of the drum, as it appears to have gone into a private collection.

|

| Photo from the Ader online auction catalogue |

|

| Photo from the Ader online auction catalogue |

Another clue to painting drums hangs in the National Portrait Gallery, a portrait of Charles and his secretary Sir Edward Walker. Walker is using an oversized drum as a makeshift desk. The drum bears a coat of arms.

It appears that emblazoning drums with coats of arms was common practice: Sir William Brerton paid £4 10s for his coat of arms to painted onto twenty drums (National Archive SP 28/225/1 fol. 3r). The Royalist Trained Band garrisoning Wythenshawe had a drum bearing the coat of arms of Robert Tatton, Wythenshawe's owner (National Archive SP28/346/1)

I tend to paint drums Foundry ochre 4B, with darker coloured rims - purely because they look really good when washed with Nuln Oil. And, no, I don't paint armorials on them.

Trumpeters had a very important part to play on the battlefield, not only giving commands to the troops via their trumpets, they also acted as heralds negotiating with the enemy, delivering messages. It would appear from the many financial accounts that exist, that captains of horse went to great expense to equip their trumpeters, both with clothing and trumpet banners.

We know that Brereton spent as much on his trumpet banners as he did on his cornets (both a princely £5 for black taffeta). Markham (Souldiers Accidence pp44-45) describes trumpets thus: "a fair trumpet, with cords suitable to his captain's colours, and to his trumpet shall be made fast a fair banner, his captain's full coat of armour". Other supporting evidence on a memorial to Captain Sir Richard Astley, of Lord Loughborough's Regiment of Horse, at St Mary's church, Patshull: this shows a military procession, the trumpeter carrying a trumpet with a banner bearing a cinquefoil, the same design as Astley's cornet. See here for more details.

I have now taken this as a cue to use cornet colours and designs as inspiration for my trumpeters.

* probably best not to ask how it was encouraged, the Japanese used boxes of urine soaked sawdust

** the difference between the two is lost on me, but no more! A reader writes clarifying the issue for me. A halberd has an axe type bit attached to the sharp stabby bit, and a partizan is a stabby bit with extra stabby bits

If you enjoyed reading this, or any of the other posts, please consider supporting the blog.

Thanks.

Superb. You should really have a patron page for donations, this blog is a gold mine! Off topic question, I was reading your links for the Trained Band regiments you have painted, what would be realistic civilian coat, breeches and sock/hoes colours to use for some of the London Trained Band regiments?

ReplyDeleteThank you for your very kind words Lewis. To be honest the blog is keeping me sane during all this C19 lockdown time; the rest of the time it's just my way of storing lots of snippets of information in one place, with pretty pictures. As I wrote in one of my first posts, this blog is by me for me, if it helps others out that's a bonus.

DeleteIf anyone wants to show their appreciation to the work of the blog there are a couple of affiliate links in my general links list (Element Games, and Wayland Games) any purchases there generate a small commission for me. (The rest of the links, I must stress are not affiliate links.) Alternatively, just click on the odd advert, as that also generates earnings via Adsense (not enough to retire on though, but enough to pay for the domain registration or the odd car park ticket).

Trained Bands - remember I paint true 15mm and wash heavily with Nuln Oil, so you might need to adjust slightly depending upon the size of your figures. I tend to pick about four colours when painting breeches - usually a grey, drab, Russian brown (which is more of a green colour), and a random 'posh' brighter colour - for one or two figures only.

Coats is similar, grey, drab, a blue, madder red, a darker brown, maybe Russian brown, and one or two figures might have a brighter coloured coat. Occasionally I might throw in a black coat for an officer (RailMatch weathered black is brilliant). As we are talking LTB quite a few sleeveless buff coats would have been present.

Stockings I usually go for just white, but this is down to laziness - there should ideally be a number of neutral shades, maybe the odd grey (there is a reference to the NMA being issued grey stockings somewhere).

Shoes, again laziness is my guiding light here - I generally use Humbrol dark earth or natural wood, officers tend to have fancier/different shades of brown.

LTB auxiliaries were recruited from apprentices and unskilled men, and there is some evidence that they were issued clothing and weapons (there's a reference that some of the Auxiliaries were issued blue winter coats). So possibly a little more uniformity for them, compared to the regular LTB regiments?

There are a number of 'colours' posts with colour swatches from a Sealed Knot living history camp which might help. You can find them under theme - 'painting guide'. Also have a look for my Trained Bands post, again you can find that tagged 'painting guide', or faction - 'Trained Bands'

Lewis you have spurred me on to add a 'support the blog' link, using buymeacoffee.

Deletehttps://www.buymeacoffee.com/KeepPowder

Good news! For me it’s just a way to show my appreciation for the help it gives me pursue my hobby plus the entertainment I have got from scrolling through almost all the regiments you’ve painted up!

DeleteThanks for the trained bands pointers, Eureka miniatures have released some 18mm EVW figs (I have their SYW range too) that have a lot of buff on their unarmoured figs so will be a good way to go- just got somee Austrians to finish off first 😬

Many thanks Lewis, really is appreciated. Although maybe I should be apologising to you for the hit your wallet will take buying a new army.

DeleteI had a handful of samples from Eureka, they really were nice figures. Shame they towered above my Peter Pigs.

Thanks for this. your painting guides are absolutely top notch and this is one of the best. Foundry ought to give you a commission as those colour swatches of yours put me onto using their paint more or less exclusively now!

ReplyDeleteGlad you are finding them useful.

DeleteAs for Foundry... there's a thought! If only! Would save me a fortune.

Many thanks for supporting the blog via buymeacoffee too. Much appreciated.

Great blog. Just one point - the halberd is the one with the axe attached, the partisan the spear with side points.

ReplyDeleteThank you!

DeleteEveryday is a school day. I shall amend accordingly.